I was recently struck by a section of Vincent Deary’s ‘How We Are’, part of a trilogy of books exploring the human state, which was recently followed by ‘How We Break’ and will conclude with ‘How We Mend’.

In it, he explores the meaning of ‘freedom’ in a social sense, and in reading it I couldn’t help but equate his words to the journey of creativity, one in which we perceive that we want total freedom in order to create whatever we want, when in reality we are likely to far more fruitful when creating within a set of clear restraints. The common adage of a writer struggling with a blank page or an artist not knowing how to make the first mark on a clear canvas is something that all of us might struggle with in various forms of life. Decisions can be so much easier when we are given a brief or invited into an existing space, group or routine, we can find our way to fit in and flourish within those perceived parameters. Sometimes we may find ourselves in a space we feel we don’t suit, so we continue searching until we find a space in which we can operate happily within. We lean on our socialisation to understand how to be in each scenario that we find ourselves, whether to assert our individuality or to blend in.

Here’s the excerpt from Vincent…

“We want to abdicate our wills in leisure, we want to be temporary Taoists. The Taoists were early Chinese philosophers for whom the ideal way of life was wu wei, or non-action. Not in the sense of doing nothing, but rather in the sense that a plant grows towards the sun. The plant doesn't have to consider and try, it just naturally does the right thing. We might yearn for this effortless and implicit knowing of the right action in day-to-day life, but we don't expect it. On holiday we do. By spending money, by employing people and placing ourselves in their pre-packaged routines, we expect a minimum of fuss and bother.”

“A walk in the park is a clever synonym for ease. Move a little on and up from leisure, away from the fun, and the rules don't change so much, only the feelings of the participants. It's obvious with christenings, weddings and funerals, the sacraments and markers of birth and death. We have, collectively, beaten paths, worn ruts to guide and channel the actions, feelings and thoughts of these occasions. There are roles for the characters, places for them to be, actions for them to perform. Ritual contains things, allows life to happen. This is no less true as you walk around the supermarket or when you visit the cinema or restaurant or when you sit down to work, when you assume your office, your place in society, the thing that you do to get the money. Our living occurs within a pre-established and overarching order, and our relationship to our place within that order is ambivalent.”

“There is an old story, one we retell a lot, where the socio-symbolic matrix, the system in which we are immersed, is the source of oppression and the hero's defining characteristics are rebellion and subversion. Usually, in this story, the system is overthrown, transformed or escaped. Occasionally, Big Brother-like, it wins. In this light we might see revolution as a refusal to walk the desire lines of posterity, as an attempt to forge and walk new ones. The rebellious spirit is pioneering, ground-breaking, romantic. Who wants to be a cog? But we are as complicit as we are coerced. Apart from the most basic mass behaviour - mob rule - the coordination of collective human beings requires a set of prescribed routines, moves and roles, props and scripts. In all this prescription, oppression may be there, but there is also a massive amount of freedom: the freedom from having to think again and reinvent, and the freedom to be with one another in complex and difficult states. In our collection of props and practices lie the possibilities of liberation and leisure, the machinery for communication and communion.”

I believe that both art and religion are significant social vehicles for communication and communion. They can both be highly prescriptive, but when presented and approached with a sensitive delivery, they each invite the individual to a space in which we understand how to be, yet can bring ourselves in order to listen, receive and maybe experience that sense of liberation.

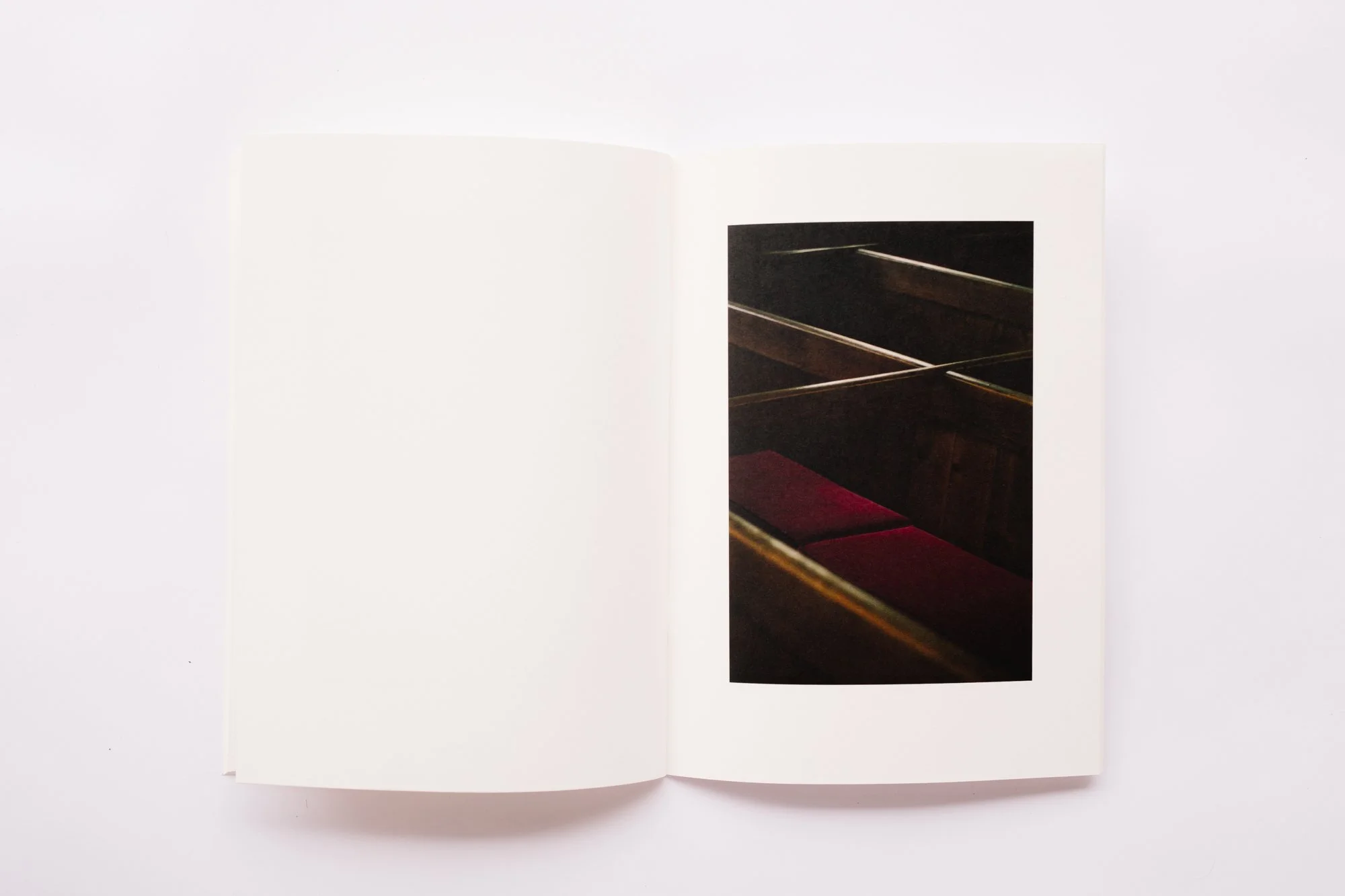

In terms of approaching that blank page, historically I have fallen into a bit of a trap of defining the end of a project too soon, sometimes before I’ve even begun. The starter-finisher in me wants to know that the task is manageable and will at some point come to a defined and deliverable end. However, I’ve recently tried to devise projects that are completely out of my control by handing over the next steps to collaborators, so that I have very little say over how they develop. However, I still need to give myself some element of framework to operate within. The world expects consistency of artists, we want to see someone create something beautiful and replicate it numerous times. We understand what they’re making and we can receive it happily. This is something I’m not particularly good at delivering, largely because I believe a project needs to be explored on its own merits, not squeezed into one particular way of working. Perhaps I just have found my true medium yet.

As an artist, you have to be proactive, more often than not you cannot wait for the dream commission or job to come to you, you have to create it for yourself. Summoning something from nothing. We dream that we too can exist as if we are a plant that grows towards the sun, to feel we are naturally existing within ourselves and doing the right thing, making progress, achieving our life’s aims and sharing our beauty with the world.

I wonder if a seed knows what its goal is before it starts to grow? Or whether it does just grow towards the sun, knowing that that is enough.